|

1. The basic premise underlying a spectrum of the arts

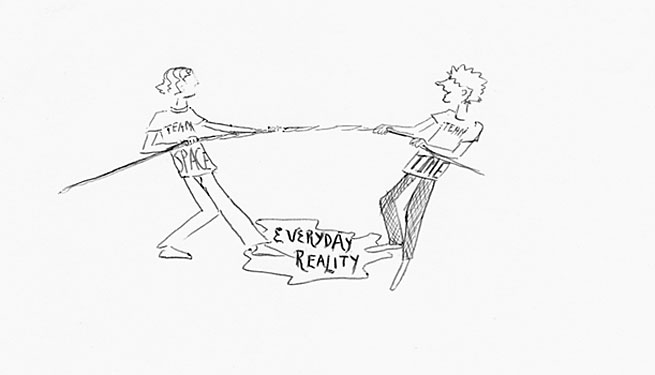

Why are the arts all of one family? Let us take a journey through the arts and find out. This book is a concert pianist's musings on the philosophy of art and how, despite their intensely individualistic natures, the arts distribute themselves according to a magnificent underlying order. It is an order though that unfolds to us only if we turn directly to our own experience of each individual art, and identify what in that experience is a manifestation of time and what is a manifestation of space. It is an order that disappears if we consider not our experience but the experience of the artist while making the work of art. What becomes apparent is that the more time has a role to play in our experience of art, the less space does, or, equivalently, the more space has a role to play in this experience, the less does time. It is from the fact of this inverse variation of time and space that we can establish a “spectrum” of the arts, where the sole variable for determining a position on the spectrum is the changing proportion of time to space. This is a startling hypothesis.

Chapter one lays the theoretical groundwork for the hypothesis of the spectrum. The remaining chapters contain a careful introspection into our experience of each art. This enables us to identify which facets of that experience are due to time and which are due to space, which in turn allows us to assign the art to a certain position on the spectrum. When the task is completed we find that the spectrum unfolds in the following order: Music (the most temporal art and the least spatial), Poetry, Animation, Dance, Theatre, Literature, Film, Painting, Sculpture and lastly Architecture (the least temporal art and the most spatial). As we voyage from art to art in the main body of the work, we gain deep insights into how we react to each art, and to art in general.

The diagram suggests how the proportion of space to time in our

experience of art alters in a continuous fashion from music, at one end

of the spectrum, to architecture, at the other1.

2. How space and time combine to form a reality

I use the term “reality” to mean our experience of a particular bonding of space and time. I quote Kant and Schopenhauer to support the premise that time and space are the two basic building blocks of the everyday reality, and by extension the other artistic realities that I propose. Henri Bergson’s illuminating descriptions of the profound differences between time and space are used to allow us to consider the philosophical unlikelihood that time and space would ever be bonded together at all. This in turn provides us with the freedom to conjecture that if they combine, they can combine in different ways and form more than one reality.

3. The everyday reality becomes just one such possibility, but an important one.

The everyday reality is formed when time and space hold each other in equal (limiting) embrace, the point halfway across the spectrum. Schopenhauer describes this equal embrace, or mutual limitation, as the law of cause and effect. It is reasonable to assume from this that in the other (artistic) realities there will be less cause and effect in evidence, that the virtual cord tying space to time is loosened, and in the case of music completely untied. Schopenhauer describes the actual mechanism by which space and time cohere in the everyday reality. He sums up cause and effect by saying that the “here” in space and the “now” in time are immutably joined. In art, then, we might expect the here to wander from the now (as in a play when we are suddenly transported from one geographical locale to another), or the now to wander from the here (as when in a novel a character sitting in a room reminisces about previous events that took place somewhere else).

4. How the exclusiveness of the term reality is not violated by there being more than one reality

Reality usually implies “all that there is.” There “is” nothing that “is not”. How can there then be more than one reality? The answer is that this exclusivity is not violated if, when we are in any one reality, it seems to us complete, nothing requiring or implying that another reality has existed, will exist, or need exist. I give examples of the unique points of intersection between pairs of artistic realities and what it is like in our experience to transition from one to another. To enter an artistic reality, we replace our everyday space and time with an artistic space and an artistic time.

5. Time is created afresh in the arts that are most temporal

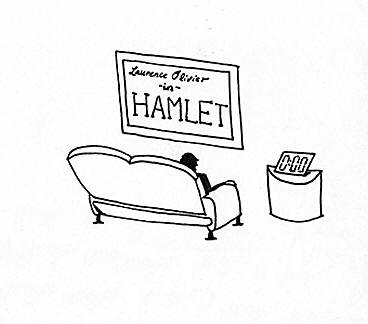

When entering the realities of the most temporal of the arts, time is always created afresh: at the start of the work there is as yet no past. This freshness persists through poetry and animation. A transition occurs between dance and theatre. In theatre, when the curtain goes up and we see a character on stage, before he has spoken a word, we attribute to that person a past. We may not know yet that this is Hamlet, or that he is Prince of Denmark, or that his father died, but we assume that we are going to learn something about this past as we go into the work's future. There is always a past prior to now. In music we do not attribute a past to the opening statement of the theme. Nothing is required to have led up to this statement. In dance things begin to get blurry. As it will be in theatre, we see a person as the subject of the work. But we do not as yet expect to learn about this person's past. Their body is merely an instrument to move, and convey things through motion.

6. We tie the senses together: a reality is forged

What does the artist actually put together in order to make a reality? It is not as if the artist can directly add time or space. He can however directly control what senses bring to our awareness his work of his work of art. Each sense has an inherent tendency to lead either outwards towards space, or within, where our experience is only of time. By emphasizing data from certain senses and de-emphasizing data from others, the artist affects the overall balance of space to time in our experience of the work, that is, the identity of the reality itself. For instance, no external sounds arrive to us directly from a painting. We may hear sounds in our imagination, but they are evoked by what we see. Ironically, because sounds are not arising externally in the work, there is a greater likelihood that the sounds we hear in our imagination will be in aesthetic accord with what we see. Music is an interesting case. What comes from the work of music is only sounds. Although sights arrive from the musicians playing, these sights are only in physical, not aesthetic, accord with the sounds these musicians are making. Sight, and with it space, has no role to play in music. Nothing from any other sense that, added to the sounds, improves upon what the music conveys by sound alone.

7. The senses do not form a complete set

We take for granted that at any given moment we may be receiving impressions through two or more senses. Yet the perceptions we receive from no one sense by itself conveys that any other sense need exist. Certain things result from this: a) there is no way to describe a sense that we do have based only on what we know from other senses we have, b) there is no way to imagine a new sense that we do not already possess, c) there is no way of attributing the term ‘complete’ to the group of senses that we happen to have. The fact of the combination of the senses cannot be assumed a priori. This helps us think of the senses as ingredients in a stew that can be combined in proportions.

8. Identifying meaning in art, so that we can ignore it

In the pursuit of identifying what in our experience of an art is due to space, or to time, meaning is often a distraction. Moreover meaning arises so ubiquitously that often we will not be alert to the fact of its presence. To help in identifying the presence of meaning, I describe four disguises under which meaning may appear. I term these: “objective”, “verbal”, “utility” and “human”.

9. The remainder of the book

A chapter is devoted to each art, starting with the most temporal and concluding with the most spatial.

"Download full text of chapter (more

technical version)" "Download full text of chapter (less technical version)"

|