|

1. Music as the art of time alone

In our experience of music time is paramount and space is virtually non existent. This assertion may elicit strong objections. The first part of the chapter is devoted to substantiating this claim.

2. The inherent differences between hearing and seeing

Sight is a sense that immediately begs the existence of space. Hearing requires nothing of space to explain the quality of our perception of sound, or the relations among sounds, in our consciousness. I make the distinction between the material cause of a sound, which is a physical occurrence in and thus requiring space, and the “effect” of this cause when it reaches the brain and we have for the first time the perception of a “sound”. The vibration of waves in space is not yet this sound: sound only lies in consciousness. Altering Plato’s allegory of the cave, I imagine a person born blind, who has heard sounds all his life but who now, for the first time, miraculously can see. Within moments he is asked to point to the object in space that he thinks corresponds to the sounds of birds (a sound he already knows). At first he sees no reason for there to be a correspondence between a sound and a physical object. Even if he accepts this premise, he has no basis on which to provide the right answer. The qualities of sounds live in our consciousness and these qualities are not altered by perceptions of sight.

3. Additional arguments in favor of space playing a role in music

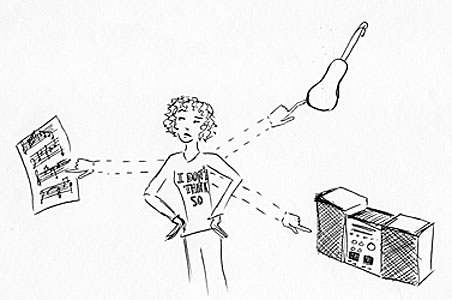

I address these arguments in turn: a) the role of the performer as a physical presence in space,

b) the spatial nature of music’s notation system, c) the spatial structure of the ear, d) the “highness” or “lowness” of a pitch. The most difficult

argument to deal with is e) that we can determine from what direction a sound is coming when our eyes are closed. In this case the issue depends on whether, without prior knowledge of space, we would still “hear directions” or only certain non-spatial changes in the quality of the sound.

In each artistic reality there is an “artistic time” and an “artistic space.” The arts in which time outweighs space I term the “temporal arts.” Temporal arts share the following characteristics: a) they are performed, b) the artistic time in their reality resides within the work of art but not outside it, c) their structure exhibits itself primarily through time and not space, d) development*, versus succession, is often the means by which structure is revealed through time. A corollary to this last is that a way has to be worked out in order for the work to remain constant to a vision of truth despite the inherent nature of time to bring about change.

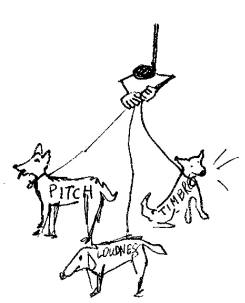

5. How sounds vary and whether duration is one

The fact that we speak of sounds in the plural indicates that there are identifiable variables in the quality of sound. After exploring the nature of the variables of loudness, pitch and timbre (tone quality), I ask whether duration is a bona fide parameter, since a given duration of time can exist with or without a sound being present. Without space duration assumes a more important role than in any other art, and is one of the fundamental ways in which one sound can differ from another.

6. A note is an abstract entity that is manipulated in an equally abstract pseudo-space

Most would identify the “note” as the basic building block in the structure of a piece of music. One of the reasons why we might assume space has an important role to play in music is that the note has various spatial characteristics. It can be manipulated by the composer in a space-like way: it can be moved, raised, lowered, have its position changed relative to other notes. The reason this seems true is that the note is not a naturally occurring phenomenon in nature, but a certain intentional way of bringing the variables (see no. 5) of sound into relation with each other and then holding them in this relationship for a pre-determined duration of time.

As such, the note is an abstract entity, and it is manipulated by the composer it within an equally abstract medium that is like space but not yet the usual space of experience. At this starting point on the spectrum, space exists in a latent or virtual state, ready to make its appearance with the next art: poetry. The properties of this virtual space can vary from composer to composer. For instance the notes in Bach’s space are more transparent: hearing one voice doesn’t prevent us from hearing another voice at the same time. In this regard, Beethoven’s space is more opaque. By modifying the properties of the notes in a piece, and assessing its effect on the integrity of the piece, we can identify the unique properties of a particular composer’s musical space.

7. Temporal effects of music

Music affects how we perceive the passage of time. Ultimately, it is time itself which is molded by music. The architecture of a phrase accelerates and retards the rate of the conscious passage of time. Even the order of events may seem to be altered in our consciousness. For instance what happens in the current moment can often determine what we think just happened a moment ago.

Harmony among sound is different than harmony among colors. When two colors combine, they form a new color, but we no longer perceive the original colors. In sound, we perceive both the originals and the effect of their combination. I examine how chords are refracted into melodies through a prism of time. There is also the temporal lens of tempo which has a decisive effect on how we perceive structure, revealing different levels of details and connections.

8. Is there another art in time alone?

Can two arts occupy the same place on the spectrum? If yes, it would abnegate the basic principle of the inverse variation of time and space as a means of contrasting the arts. Before leaving the current position on the spectrum, it is therefore important to ask whether there can be another art in time alone. A particular possibility is considered, one that uses colors by themselves in a way that removes all references to space. While affording some fairly interesting experiences, it is not rich enough to form the sensuous underpinning of a robust art form, but is best used reincorporated into more spatial arts that use color.

* Development conveys the notion of organic growth where each stage in time depends on the those prior to it, so that the order could not be changed. It would be unnatural to see a flower in full bloom attached to a stem that had just barely emerged from the seed. It would be unnatural if the right arm of an embryo developed fully before the left arm began to develop. These inorganic exceptions are what happens when mere succession replaces development. Succession can be thought of as starting with organic growth, which exists as a seamless whole in time, removing time, so that the whole can be separated into parts, re-ordering these parts using space, then transferring this order back into time.

"Download full text of chapter"

|

.jpg)

.jpg)