|

1. Sharing space

With sculpture, the work of art can safely enter our everyday space without compromising its spatial properties, by being impervious to time. Unlike with painting, the spatial properties of a sculpture are not jeopardized if we physically interact with the work. Unlike painting, the work will change its appearance if we move relative to it, but this only serves to underscore its spatial properties that remain constant in time. In fact the abiding spatial identity of the work becomes apparent only as a result of our motion through time.

2. The occupation of space

While it is traditional to define space as the possibility of extension, for the purposes of the spectrum another quality of space deserves attention: the ability to be occupied. This entails a paradox, for when space is occupied by an object, it can only be perceived up until the boundary of the object, we can no longer verify the extension of space within the object. Thus sculpture, by occupying space, withholds from us its own inside.

Its surface reflects back our attempts to know within. The nature of the inside as inside remains unknown. We may try cutting into the sculpture to see its inside, but that only produces more outside, and the inside continues to retreat farther within.

If we cut entirely through the work, the inside vanishes even as a possibility, and all we have is outside.

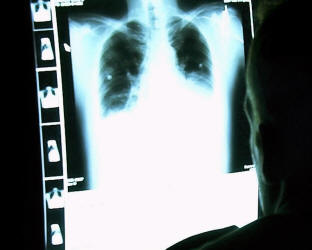

Even an x-ray shows us only the outside of something previously unseen because within.

3. Experiencing the whole of the work in time

Painting creates an entire space within its frame, which can then be populated by a multitude of objects. Sculpture is but a single object among a multitude of objects in a shared space. The price we pay for painting creating an entire space of its own is that we cannot move among its objects. With sculpture, this problem no longer exists.

A sculpture completes itself in space by rounding back upon itself into the third dimension; in effect, wrapping space around itself. As it does this it both cuts off its inside from its outside and its back from its front. To see the entire sculpture we are forced to “dance” with it (move in relationship to it) through time. Though we are the one moving, we have a silent partner (the work’s form) that reveals its presence through its secret choreography. As we walk around the work new material buds out of old until what is old arises out of what is new. In painting, our time was sufficient to see the entire work. In sculpture, our time would have to be endless in order to compass the work in every perspective, from every angle, from every elevation.

The whole of the work remains forever beyond the present in time.

4. Touch

Unlike painting, we can touch a sculpture as well as see it (notwithstanding societal rules against touching works of art). With a painting, if we touch the canvas we feel pigments and the represented reality dissolves. Something similar but not as severe happens if we touch a statue and find that we are feeling wood or stone instead of flesh. The reality is not so much dispelled (as it is with painting), as we are offered an equivalent but different, competing reality. Touch is the limiting case of sight when the distance to the perceived object shrinks towards zero. Holding an object in our hand is like seeing it at a distance of zero with a thousand different “eyes”, each located in a different place: all limitations due to visual perspective are removed. If the sculpture is too large to hold in our hand, then if we stand far enough back from it, it seems to fit into our hand, and we can respond to it with ideated sensations of touch.

5. A sculpture affects the space around it

Sculpture enters our reality not so much to become a part of that reality as to try to influence it: proposing an alternate reality in place of the everyday reality. From the work’s hidden center, in the hidden heart of space, the sculpture reaches out to enter our space.

It affects its immediate surroundings as a magnet affects iron filings. This effect is maximized if we find ourselves in an environment populated only by statues: we become the exception and feel that we cannot suspend our time to fully enter the works’ reality.

6. The attempt to reveal the inside of the work

The inside of space remains a mystery but the sculptor can take pleasure in suggesting it through the behavior of the outside of the work, as for instance the sense of swelling and receding of surfaces. From what do they swell, into what to they recede? Surfaces can appear eroded away. A sculpture could be composed of closely spaced, hanging strips of cloth, into the midst of which we can walk. This would offer touch and sight an ambivalent feeling of being inside and outside at once.

7. Comparing sculpture with painting

If painting is thought of as two dimensional (2.0), then sculpture, in reaching for three dimensions, ends of exploring the fractal dimensions between 2.0 and 3.0. Works barely incised on a flat surface are closer to 2.0 while those that are in the round are closer to 3.0.

When we look at a painting of a city, we assume the city continues beyond the edges of the picture’s frame. While sculpture influences the space around it, its influence also can be flatly contradicted by what we unavoidably see behind or near it: because all are in the same space. In painting the everyday reality itself as a whole is denied entry into the work’s space. With sculpture, the everyday reality never fully lets go of the work. The surfaces of a sculpture create possible “canvases” on which to paint. In this limited sense, sculpture may be said to “contain” painting. During the creation phase, the sculptor takes matter and re-forms it, while the painter creates in the first place the appearance of matter, as well its form.

Stained glass, like painting, reveals a space inaccessible from our space, but unlike painting can be seen from both sides. It is a tenuous membrane representing a third spatial reality suspended between two other spatial realities, one everyday and one architectural.

8. Comparing sculpture with dance

Dance and sculpture occupy midway positions on their respective sides of the spectrum. In an extreme case, the dancer can remain motionless. In an extreme case, a sculpture can seem as if it is about to move. In the first case, there is a halting to motion whose inertia we still feel. In the second case we are alert to every sign that motion may be beginning.

A mobile (in the style of Calder) is analogous to a dancer who can move any way he wants as long as one part of his body remains fixed in space. Because of this restriction we can predict the entire region of space that either can occupy. Time adds nothing unforeseeable but merely “works out” what is latent in the articulation.

"Download full text of chapter"

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||