|

1. A review of space on the spectrum

In music space exists in a virtual state. In poetry space is created as an epiphenomenon to the meaning of words, and can vanish and reappear. In animation, space withstands changes in time. In dance, space is actively created by movement. In theatre, space is still relatively primitive. While it is needed to house content, it is there more to provide resonance to action by virtue of being empty. In literature, the narrator takes a stance in space outside the action, from which he controls the flow of time, the flow of the time of the action slows down. In film the work is not yet strong enough to maintain its spatial properties in the event of our physical interaction with it. If I apply enough pressure to the film screen, I will distort the shape of the images projected on it. I can affect how their appearance changes with time. With painting the stability of content through time is no longer an issue, but the spatial properties of that content still cannot successfully withstand our physical intervention: my hand can puncture its reality. It still requires the artist to conjure into existence a spatial reality in which it can live beyond the reach of our actions. In sculpture, the medium of the work can withstand interaction with us and so can enter and share our space. When we move on from sculpture we take with us a question about space that sculpture raised for us, a question that it is for architecture to try to answer.

2. What is the nature of the inside of occupied space, i.e. the space that we cannot see? Architecture answers by turning sculpture inside out

The question that sculpture raises about space is: is what goes on in the inside of a sculpture, where we can not see or explore, also of the nature of space, or is there a secret heart to space from which space is born but which is of a different nature than space? The answer to this question about the inner nature of space is left to the end of the spectrum. Architecture provides a provisional answer: what goes on inside a sculpture is just more space, not a withheld mystery. The architect simply hollows out the inside of the sculpture while making it big enough for us to stand, and then turns the sculpture inside out so that it surrounds us. Symbolically the entry way to a building is a fulcrum by which our movement causes space to turn inside out. The skin of the sculpture has been lifted away from the body of the sculpture, stretched to reach around us and joined behind us. We are in the inside and can examine its nature for ourselves. All that we find, all that architecture offers us as to the identity of the inner nature of space, is that it is simply more space: a void within that is essentially the same as the void without, but for the fact that the new void is enclosed rather than enclosing. Architecture is still the most spatial art though because it comes closest to answering the question of the final nature of space. As music began the spectrum with the inner nature of time, so architecture ends the spectrum with an assertion regarding the inner nature of space.

3. That we find ourselves at the center of this inside

Is there then no heart to space? The search is not quite over. If we look to the very central point in the space we see around us in the work of architecture, we find ourselves, i.e. we find consciousness in time. We could not see beyond the sculpture’s skin, but through affection we can go within our skin. At the beginning of the spectrum, in poetry, space is born out of time, and at the end of the spectrum, in architecture, where the shape of the inside is designed as a lens to focus space on ourselves, space collapses inwards into time. The spectrum begins and ends with space emerging out of and then returning to time, suggesting that the spectrum does not terminate on either end, but joins together into a circle*. This would place the self and the everyday reality at diametrically opposed positions, each surrounded by the arts.

* This may explain the profound affinities that many have noticed between architecture and music, affinities belied by their apparent distance on the spectrum.

4. Architecture usurps the everyday environment. It becomes a study of our relation to space in general.

By surrounding us with itself, the work of architecture has appropriated the everyday environment, and replaced it with itself. To successfully stand in for the everyday environment it will attempt to meet the needs that we experience in the former. For instance, instead of a sun, it may provide other means of light and warmth. Additionally it can pursue its own ends independently of what the everyday reality normally provides. It may decide selectively to let in parts of the outside environment: for instance light but not air, or air but not light. The building by its spatial properties can exert control over the sort of activities of everyday life that can go on within it: eating, sleeping, shopping, using a bathroom, having a meeting, etc..

While we explore the spatial relations between parts of other works of spatial arts, in architecture, the work becomes a study about our relationship with our spatial environment.

5. Our reactions to architecture include directly data from all our senses

Architecture does not so much use the everyday space given to it, as it appropriates that space, wholly redefining it into an artistic space. The price for this usurpation is that it must pay heed to everyday causality (e.g. it must stand up and not collapse).

In that architecture stands in for our entire environment, it is legitimate to say that any sensation we receive from that environment, whether it be through sight, hearing, smell, touch or any other sense, is part of our aesthetic experience of the work. Thus our experience of a work of architecture is just that, our experience while within the work. Our sense of balance, for instance, is activated by the inclination of the surfaces we stand on, and this part of our sensation of the building. Pressure, due to gravity, gives us a more complete sense of contact with the floor than we received through our hands with sculpture. Lighting, sounds, heat and cold, the aromas of plants, air conditioning or food, impact on our state of mind. From architecture we receive, directly from the work, input from more senses than any other art, and is another reason why architecture exists so close our inner self on the spectrum. The work may or may not attempt to control what is available from each of these senses.

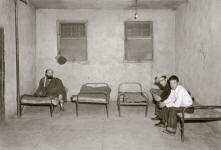

A building is semi-permeable membrane that selectively lets in certain sensations form the outside, while diminishing or barring others. A jail is an extreme example. If there is central air conditioning, temperature and olfactory stimuli unique to different parts of a large building become homogenized, nullifying in part the spatial articulation of the work. The way the senses to act in concert in the everyday reality affects our reaction to what happens if one of the senses is open to the outside and another is not. We see a car passing in the street through a closed window, but we do not hear it. Outside we see the snow falling and the wind blowing but we are comfortably warm on the inside.

Sounds within a building are strongly influenced by shape and materials. When we walk into a new room we notice a sudden change in the quality of background sound. If we are talking at that time we notice that our voice quality suddenly changes. The music auditorium is a work of architecture, where space is designed with sound properties in mind.

By default, architecture “houses” most of the arts, including itself when there is a smaller building within a larger one.

The space of architecture affects both our body and our spirit. Convex surfaces push inwards upon us through the intervening space creating ideated sensations of pressure on our body. Claustrophobia is an extreme example of this. Lofty ceilings and high recesses produce the opposite effect, and we seem to enlarge.

6. Of the spatial arts, architecture exerts the maximum control over time by space

All points in a painting are accessible to our eyes at a same time. To see all of a sculpture we must walk around it. Sculpture we must move around, but in architecture we must move through it to see it. The structure of a work of architecture, through the articulation of its sub-spaces, controls limits the possibilities of how we can get to know the entire work through time. Repetition of content in space (the great temple with rows of columns or the great cathedral with repeating windows) create a sameness of content that belies our attempts to change that content through time by our movement in space.

7. The principal differences between inside and outside

Contrasting architecture with sculpture in many ways is to contrast our experience of being on the inside with that of being on the outside. Years of experience going back forth between the two has allowed us to forget some of their incompatibilities, for example that given a view of the outside of a building there is little way to imagine what the insides looks like or feels like,

While we can experience architecture from within or without, the current position on the spectrum has to do with experiencing it from within. The latter experience (from without) was treated in the previous chapter. Even on the inside though, there are “outside” experiences. For example, the experience is sculptural whenever one part appears convex to us relative to it surroundings. The “space” of architecture is both the shape of the empty space bounded by the floors, walls and ceilings of the work and the shape of the latter things themselves when they stand out in relation to the background.

Because of its relative size, our usual experience with sculpture is that it will change appearance in response to our movements through space. Seen from afar, a great cathedral defeats such movements by remaining constant in appearance, at least until we have moved a substantial distance. In this the large work of architecture is being rather un-sculpture-like, being more spatially independent of our personal time.

8. More comparisons between architecture and sculpture

The work of sculpture is its own physical substance. The work of architecture is more at being the empty space that is surrounded by the physical substance. Sculpture is embraceable; architecture embraces. The space that includes ourselves and the sculpture is infinite in extent; the space when within that includes both ourselves and the work of architecture is finite. While we can move around a sculpture, we cannot move around architecture because it has already been “moved” around us. It did this outside of our time, during its creation-time, whereas it requires our present time, our experience-time, to move around the sculpture.

9. Experiences and structures that blur inside and outside

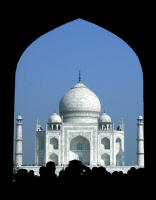

The following experiences are ambivalent regarding inside and outside. A) When sailing out the ever-widening St. Lawrence River, when do we exit the boundaries of the shore and enter the boundless ocean? B) A building in the shape of a Chambered Nautilus (but without separations between chambers). Though the work is entirely an ‘outside’ there comes a point when we feel we are inside rather than outside. C) A triumphal arch acts as if it would lead us from one reality into another.

When we emerge from under it we find that we are in the same reality as before,

but our appreciation of this reality has undergone a metamorphosis by virtue of the passage.

D) A suspension bridge’s inside is its outside: it is as if by ages of erosion only the skeleton of a structure is left. It is thus with the Eiffel Tower. They are pristine ruins.

E) The “Statue” of Liberty is large enough that we can enter its inside, though its aesthetic is designed more to be seen from the outside and not experienced from within.

The same is true of the St. Louis parabolic arch, whose impact as a soaring parabola requires that the interior be very cramped. F) If outside and inside communicate too much with each other their difference can blur. If there too many windows, all open, the inside begins to take on many the qualities of the outside, including light, odor and climate. The two can also blur if there is too little communication between them, for if we remain forever within, without doors, without windows, the walls ultimately become horizons and the roof the sky. G) Through a window, part of the outside space becomes part of the inside space. H) At the center of a building may be a room that is open to the sky. Four buildings can enclose an outdoor square. The open space between the arms of a spiral-shaped building are outside, but are still enclosed by the building. A building in the shape of a giant Klein bottle has no inside geometrically distinct from its outside. If we are inside a giant sock and a titan took it and turned it inside out, we would suddenly find ourselves on the outside even though we haven't changed our position in space. We do the same thing ourselves whenever we go through a door that goes from outside to inside (though every door contains the promise of going further within).

10. Comparisons between architecture and other arts besides sculpture

When we are in a building and look out of a closed window, the window acts like a painting, holding within its frame a reality that, for the nonce, we cannot enter.

If dance creates space via (motion in) time, architecture creates space by space. The properties of the dance space are detectable in the types of motions permitted the dancers. The properties of the building space are noticeable from what types of motions we are permitted within it (we cannot walk through a wall to get into an adjacent room; only a finite sets of paths can lead us from one end of the building to the other).

11. Conclusion.

In spite of their important differences, mankind has always felt that the arts are of one family. Many attempts have been made to provide a theoretical basis for this feeling of community. I have offered the spatial-temporal spectrum as my contribution to this question. In the future an art may arise that undermines this principle, though film and photography, unforeseeable centuries ago, fall comfortably within its definition.

Thus ends the journey through the arts.

"Download full text of chapter"

|