|

1. The creation of space through motion

Dance is the art of motion. Through motion dance creates space and defines its properties. Motion has both spatial and temporal aspects. The quality of a motion lies primarily in time. To prove this, I consider what would happen if a dancer left behind him a trail in space as he moved...

Soon everything temporal about the motion would change into something spatial. At that same point motion itself would become unperceivable, because it would become locked in a matrix of spatial forms created by the previous motions of the dancer.

2. The human body has an unchanging identity in space

If we were to ask what is changing shape in a work of animation, chances are we can only provide a temporary answer: “It is a circle that is changing shape.” However, once the circle changes to, for instance, a square, we have to update our answer and say, “It is now a square that is changing”.

[Geek: Animation. Polonius: add caption with quote of text from Hamlet]

With dance the spatial identity of what is changing remains constant through time. It is always the human body which is undergoing changes (although the choreographer can take great pains to try to disguise this fact). Additionally, there is a change in emphasis: change in form begins to take second place to quality of motion of that which is changing. Also, more of a dialogue opens up between the two.

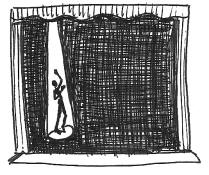

3. Space is now shared with the viewer

There is no barrier between the dancer’s space and our space. As we approach the dancer, we enter the artistic space and leave the everyday space. We can interact with the dancers and affect the future course of the dance. If we were to do this with a work of animation, at most we might temporarily block a projector.

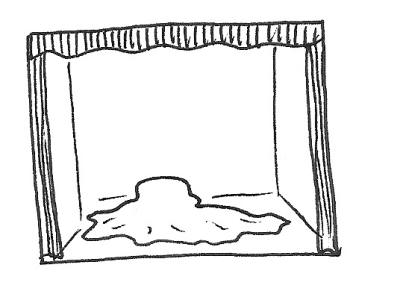

4. Dance creates space as much as it passively uses space

As poetry reenacts the creation of language, dance reenacts the creation of space. Dance occupies a position on the spectrum where space is still relatively new. Time is still paramount, otherwise a photographic image of a dancer would be a dance. Does space pre-exist motion or can motion create space? Both can be true in dance. A large piece of fabric, large enough even to cover an entire stage, is bunched up so that it barely covers a single dancer lying underneath. The dancer begins to move and the fabric as a result begins to stretch and unfold.

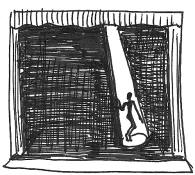

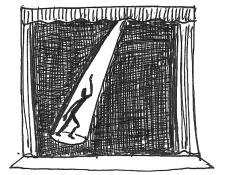

How the dancer moves affects how the fabric expands. The cloth fabric is a metaphor for the fabric of space itself. A scientific analogy is the creation and expansion of space after the Big Bang. On a totally dark stage, the narrow beam of a spotlight illuminates a solitary dancer.

The dancer moves; the spotlight opens up its focus to include where dancer was as well as where he is now. One doesn’t need an actual cloth or an expanding circle of light to sense this expansion of space.

Even if extant, space can remain passive until actualized by motion. A dancer extends his arms to form a circle and creates a new space within that circle. As a dancer moves into a new position, the space of that position changes from the theoretical state being capable of being occupied, to the active state of being occupied.

When a motion connects two positions in space, the space in-between becomes charged by the motion. This notion of a charged space appears again in theatre (the next art on the spectrum), only there space is charged by a “human action” and not a physical motion.

5. How the dancers’ motions define the properties of space

The properties of the abstract space in music were deducible from the ways notes could change and combine in a piece. Similarly, the properties of a dance space are deducible from the types of motion that are executed within it. If a certain motion does not appear at all in a given dance, or is executed with real or feigned difficulty, then in the artistic space (versus the everyday space) that motion is not within, or barely within, the set of possible motions in the geometry of that space. The success with which a dancer creates an artistic space versus an everyday space depends in part on making motions that are easy to execute in the everyday reality seem more difficult, or motions that are hard in the everyday reality seem easier.

6. Experiencing motion from within, that is to say, in time

Information about motion is communicated to us from space via sight. How we respond to this information goes beyond the spatial. We also intuit the dancer’s motion as if our own. A complex orchestration of nascent muscle contractions, which are not yet like physical effort, provide us with a purified, internal sensation of the quality of the motion. These internal sensations exist in time rather than space and bring us closer to the quality of the motion than does space. If our perception of motion were purely spatial, watching a dance would be no different than witnessing a series of sculptures in different spatial positions.

7. The role of cause and effect in dance

In chapter one I said that it was in the experience of the viewer that we should seek for space and time, not in the experience of the artist while creating the work. This distinction is especially important in dance. The performer, as re-creator, is subject to the limitations of cause and effect in the everyday reality. His efforts, though, create an artistic space which, from the point of view of the experiencer, deviates in part from the everyday reality. This deviation however cannot be as great as in animation, which lies further from the everyday reality.

8. The relation of dance to the other arts

In this and succeeding chapters the current art is contrasted to the arts in the preceding chapters regarding their use of space and time. From poetry to animation to dance, space changes from being imaginary, to external but non-enterable, to external and enterable. The same sequence occurs later on the spectrum, from literature, to film and painting, to sculpture.

"Download full text of chapter"

|